When is a knowledge graph open or closed world? And how to create a company wide implementation strategy

This week, I created my very first personal knowledge graph. It was a rather small one. One that built up on my knowledge about Star Wars. I’ve been following a course on HPI (Hasso Plattner Institut), and this topic is also important at work. So, I wanted to dip my toes in the water with a domain I’m familiar with. The graph is small: ~10 nodes and a couple of edges. I recognized that modelling a graph can be done in different ways. When you ask ten different people, you might get ten different perspectives on the world of Star Wars, resulting in slightly different versions of a graph. As I discussed my graph with co-workers, we were talking about the way I modelled the gender. I thought of it as an attribute of a person, whereas you could also model it as its own class. That would result in an edge from a person to, for example, “female”.

This was the beginning of a discussion about the “Open World Assumption (OWA)” and “Closed World Assumption (CWA)”. A concept I hadn’t heard of before. In an open world, you basically say whatever you don’t know, or what you are not able to deduce from the graph, is not assumed false or some sort of default value. Here’s an example: For Yoda, I didn’t specify the gender because I never really heard that Yoda is male. I assumed, but didn’t know. So, leaving this information out of my modelling makes it not possible to conclude the gender of Yoda.

On the contrary, a closed world assumption means that what is not known is false. For example, if I were to model that Luke does not have a sister, we conclude that he hasn’t one. Well, if this sounds a bit off to you because your belly tells you there is something wrong with this, then you are right. When I heard this first, I found this confusing and convenient. Because if a knowledge graph is open or closed world depends kind of on the view of the person who sits in front. What if I said, “OK, Luke has no sister. I see this as open world. Maybe he actually has a sister!”

Before I elaborate, I want to clarify this:

- Open World: We assume incompleteness

- Closed World: We assume completeness

I can imagine that, when modelling a graph, we are most of the time in an open world assumption. When I want to work with this graph by writing a piece of software that queries the graph for information, I might end up with a closed world assumption, because I have to decide practically.

Let's see: I write a query that lists me all Jedi mentors that are male. I realize then Yoda is missing! Now, to include Yoda, I would make a tradeoff: I specify that each node that does not have a gender is considered as male (I could have done this the other way around, with female). By doing this, I kind of shift from “incompleteness” to “completeness” because I define that the missing value is treated here with “male”.

How do you build similar knowledge graphs across a company?

What I’ve written before shows that it can be difficult to have a certain style to model knowledge graphs. A gender pay gap researcher would certainly see gender as its own concept, and therefore give gender a more important role, which results in a class and many more variations of the instantiation of a node. The question is: how do you get some sort of shared concept? I learned at SICK that you need some organization within your company that sets the course for knowledge graphs, a KG CoE, so to say. They create an upper level concept of entities and need to carry the knowledge of how to model graphs into other teams. They should do workshops to create a common wording, explain the company concepts, show pitfalls, and build a community. It’s already difficult to justify knowledge graphs against management, but if enough units create graphs, they need to be connected. It’s not that they must be connected. It’s fine to build a small world in a domain, but best practices need to be passed on.

How IKEA builds knowledge graphs

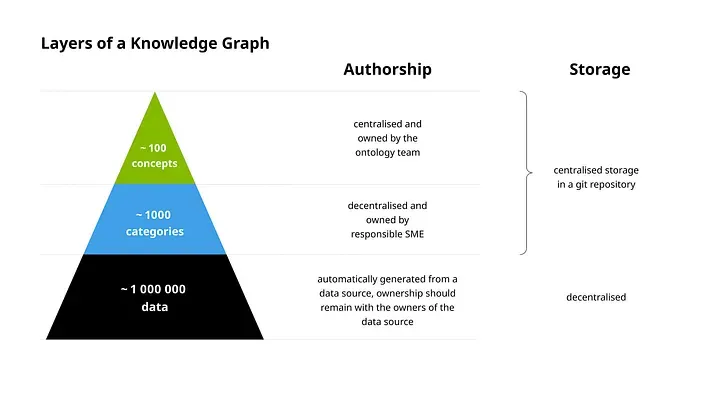

There’s an article on Medium from Katariina Kari who works at IKEA, in which she describes their KG strategy consists of three layers. The top is the layer of concepts that you can map to what I explained in the section before. The second is categories, the third, data. The concept layer would be the ontology of your knowledge graph. It contains classes and properties. Their categories are something like “bookcase, sofa, or coffee table”. It’s their vocabulary. The base layer (data) is then the actual products.

The interesting part is how this KG pyramid affects the work at IKEA. They describe that the concept layer is defined with governance policies (by the ontology team), and categories are described as domain expertise needed. So, they must have some sort of workshops for this. Their data layer is very large, and the creation of it is automated.

Thank you for reading! 💙 I share what I learn about software engineering (mostly Python), AI, product development, and life as a dev.

Subscribe and follow me on my journey. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

🤗✨ If you enjoyed this article, it would mean a lot to me if you shared it on social media or forwarded it to a friend. I write in my spare time, so any support is welcome.