Static Protocols in Python: Behaviour Over Inheritance

The first time I read about protocols was in the book "Fluent Python" by Luciano Ramalho. This book goes deep. Deeper than I knew Python at that time. If you hadn't heard of Protocols before, I'll give you a short introduction.

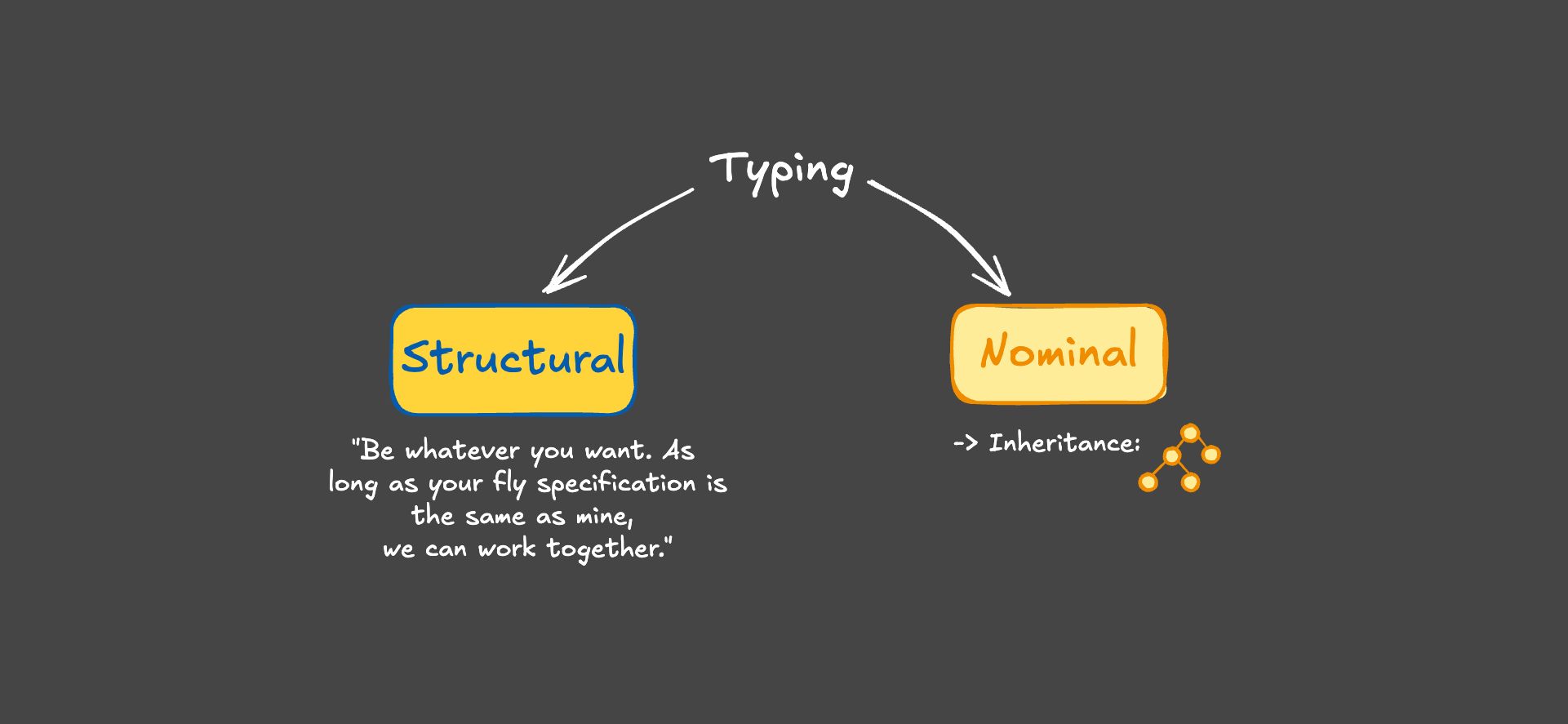

Protocols have something to do with typing. With protocols, you can check whether an object is valid based on whether it has the right methods and attributes. The idea is to check for behaviour instead of inheritance. Protocols extend Python's type hints by allowing to define structural types. They can be very confusing at first and difficult to understand, especially in a real-world scenario. In my opinion, that's partly because, for the concept to click, one must mentally move away from pure object-oriented programming. This is mostly done with inheritance. But it's also difficult to understand, because I think it's an advanced concept. Typing is also a gradually evolving topic in Python, with a naming scheme that has also evolved gradually and which is sometimes difficult to grasp, too.

Generally, we distinguish between dynamic and static protocols. This article is about static protocols.

What's mostly used - Goose Typing

It's best to start with a short example. Before I knew protocols, I had used isinstance to check for a type. This is also called goose typing. Mostly this is used when one wants to check if an object is of a specific type during runtime. During runtime is important here. Here's an example:

def fly_to_moon(something):

if isinstance(something, Spaceship)

spaceship.fly()

else:

print("Ain't flying to the moon with this")Usually, goose typing is used with ABCs and abstract classes. The concept aligns very well with the human brain. With inheritance, we can bring structure to chaos. It's neat. Most of the time, developers think about the domain they develop functions for, and then come up with an inheritance tree that's very carefully crafted for that domain. In the scenario above, we'd have a base class of Plane and a class Spaceship that inherits from Plane. It inherits a fly method along. What I do not like about this is that, in application software, I do not want to limit the possibilities upfront by using inheritance. Secondly, with inheritance, we introduce tight coupling, which is a drawback.

Static Protocols

Protocols come with the idea that an object should behave in a certain way (structural typing), rather than implementing a certain interface or inheriting from a base class, which is also called nominal typing.

Short Intro

Structural means we care about the behaviour. So, as long as we have an object that supports a fly function, we are pretty happy with it and think, "Okay, you apparently have all you need, let's go". Here's how we would adjust our example from above to use protocols:

from typing import Protocol

class MoonFlyable(Protocol):

def fly(self): …

class Superman:

def fly(self):

print('I am not a plane but still able to fly to the moon 🚀')

def fly_to_moon(who_knows: MoonFlyable):

who_knows.fly()Now, our construct is not only cleaner than goose typing and reduces coupling, but also enables static type checkers like MyPy, PyRight, or ty to pick up on compatibility before we run the code.

While you can write fly_to_moon(new Superman()) , a static type checker will complain about fly_to_moon(new Car())

Remember, all we ask for is a specific behaviour to be fulfilled. This gives us greater flexibility in our software design. Here's my take on illustrating this:

That example is a bit artificial, but serves perfectly as a short intro.

Real-World Example

Real world code is mostly more complex than this, and when I read tutorials, I most often wish to see something a bit more difficult.

As a software engineer in the AI field, I sometimes need load different trained models for certain projects. A very basic machine learning use case is to predict a class, and we have different models that predict different classes (e.g. cats or dogs, not Python classes) in different ways. You often see ABC here, but, as I said before, I think you lose flexibility this way. With protocols, each developer on the team can create, train and predict without extending an inheritance tree. I prefer to program functionally as I favour composition over inheritance, but others can code object-oriented and the code remains compatible.

Here's how this looks like:

from typing import Protocol

class Predictable(Protocol):

"""Protocol for models that can make predictions (Used for API)."""

def predict_top_k(self, query: str, k: int) -> list[str]:

...

class TfidfPredictor:

"""Predictor class for TF-IDF model to get top-k predictions."""

def __init__(self, model):

self.model = model

def predict_top_k(self, query: str, k: int) -> list[str]:

"""Predict top-k classes and their probabilities."""

# code ommitted because not relevant here

tfidf_model = load_model(model_path)

ml_models: dict[str, Predictable] = {}

ml_models['tfidf'] = TfidfPredictor(tfidf_model)The TfidfPredictor is really just a wrapper that contains only the predict_top_k function the protocol wants to see. This demonstrates how I would store loaded models in a dictionary, using the Predictable protocol as the value type. We can then run the predictions in a 'duck typing' manner based on this.

Alternatively, we could use the protocol class for our inference method.

tfidf_model = load_model(model_path)

predictor = TfidfPredictor(tfidf_model)

def run_inference(model: Predictable, query: str, k: int) -> list[str]:

return model.predict_top_k(query, k)

y_pred_k = run_inference(model=predictor, query="Classify this text", k=5)Now, if you look at the code, you see that the TfidfPredictor is completely independent of implementing any ABC. All we care about is that the model we pass to our dictionary or to the run_inference function is compliant with the Predictable protocol.

Limitations of Static Protocols

Keep in mind that protocols do not guarantee that, at runtime, the type is enforced. If you need to check during runtime, you would need to decorate your defined protocol with @runtime_checkable. Then, you could use isinstance again: isinstance(obj, Predictable).

Small Detour to Duck Typing and Static vs. Dynamic Protocols

When I say duck typing, it has to come with the very famous saying: "If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.". This saying provides you the interpreter's view on an object. As long as an object provides the required behaviour (e.g. the quack() method), it will be used as a duck, regardless of its actual type. This should sound familiar to you from static protocols. Both are behavioural. The main difference is that your IDE or a static type checker won't give you any hint about the correctness of the signature. Here's an adapted example from the Duck Typing article on Real Python:

class Duck:

def fly(self):

print("The duck is flying")

class Swan:

def fly(self, height: int):

print("The swan is flying")

birds = [Duck(), Swan()]

for bird in birds:

bird.fly()In this example, my static type checker (Pyright) doesn't tell me that we need a height for the Swan object to run the fly method. Duck typing is used with EAFP, and I like it. Static protocols extend the idea and make it safer to program, catching possible runtime errors during development time and not runtime. Small side note: Structural (sub)typing is also called static duck typing.

Conclusion

This article was about static protocols, also called static duck typing. It's baked in Python since version 3.8. Before that, we'd had already informal interfaces, also called dynamic protocols. The naming is sometimes confusing, and I have to look it up from time to time myself.

The difference is that a dynamic protocol does not have to be fully implemented and it cannot be verified by a static type checker. An example of a dynamic protocol is the Sequence protocol, which requires the __getitem__ and the __len__ ; however, it also works only with __getitem__.

To me, the main advantage of static protocols is the ability to write loose coupling code, not to run in an increasingly complex construct of inheritance, and, most importantly, to provide a way to specify a specific behaviour (structural types) instead of nominal types. Hence, in a project, it becomes easier to bring different developer styles and libraries together. One might write more functional code, another more object oriented. Besides that, it's cumbersome to make different libraries (machine learning world) work with each other in own pipelines.

If you want to read more about static protocols, I can recommend the original PEP 544 – Protocols: Structural subtyping (static duck typing) .

This was a short primer on using static protocols in a real-world project. Ever run into issues with ABCs (too big to touch, too complex?!)? Let me know!